William Blake and Maurice Sendak

WILLIAM BLAKE AND MAURICE SENDAK

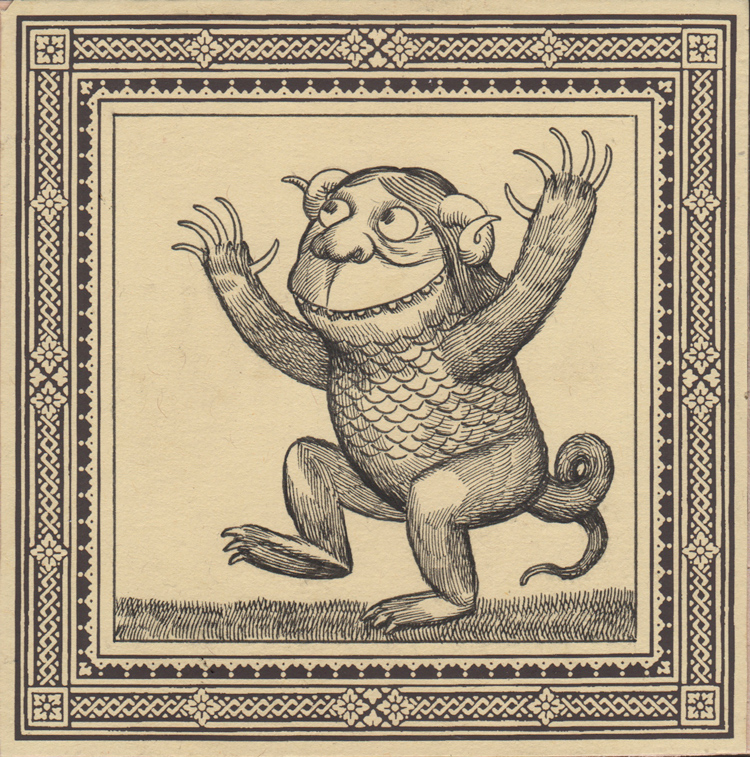

Both of these artists were known for their greatness in both visual art and writing. There is an obvious aesthetic similarity. In fact, I would suspect that much of Sendak’s style was shaped by an early influence from Blake’s art. Most importantly for this comparison, both of these artists viewed themselves as spiritual guides and defenders with a great responsibility.

Blake used Christianity as the starting place to describe the complexities of the mind and allowed an increasingly scientific culture a familiar framework to begin to understand psychology.

Sendak, who was an atheist, saw himself as a defender of children against the confusion of adults. He described the untethered, violent, chaotic, creative, free aspects of the childhood mind and gave children permission to explore the inner location where those “wild things” reside. With love and care he gave room for that intense energy, but guided them through it with calm and love.

Kerry James Marshall and Hans Holbein

KERRY JAMES MARSHALL AND HANS HOLBEIN

I don’t usually write these essays based on connections and analogies that the artists intended. I’d much rather find lateral channels through which differing artists and disciplines deal with the same themes, phenomena, mood, forces and so on—in ways often unexpected even to them. I make an exception this week however with a piece that is undoubtedly connecting itself to the past with full knowledge.

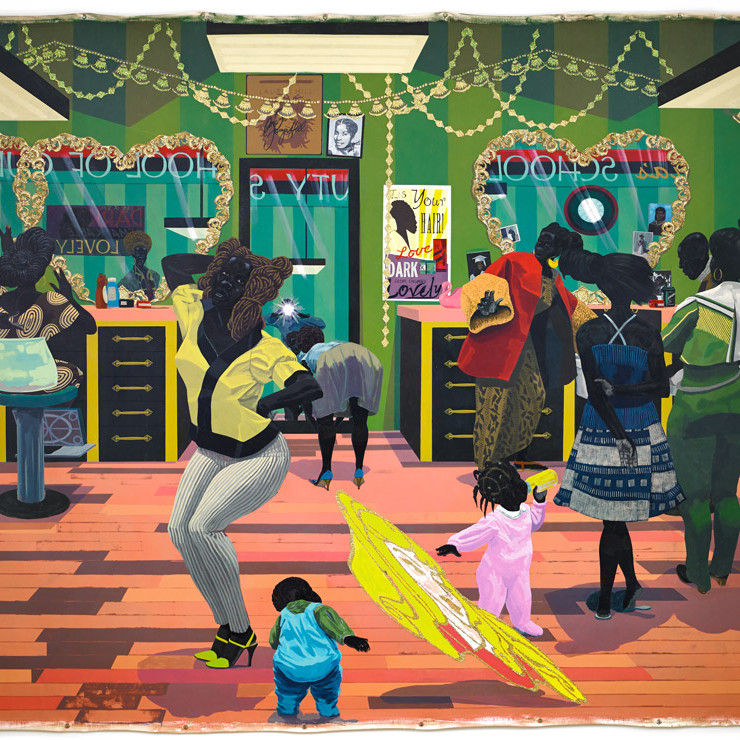

It is difficult to express just how excited I was when I saw School of Beauty, School of Culture for the first time. In it, one of my favorite living artists, Kerry James Marshall, makes reference to two of my other favorite painters (from the distant past), Hans Holbein and Jan Van Eyke. People familiar with my work know that these three artists are among those that move me the most and I have often bitten styles and methods from all three for my own purposes.

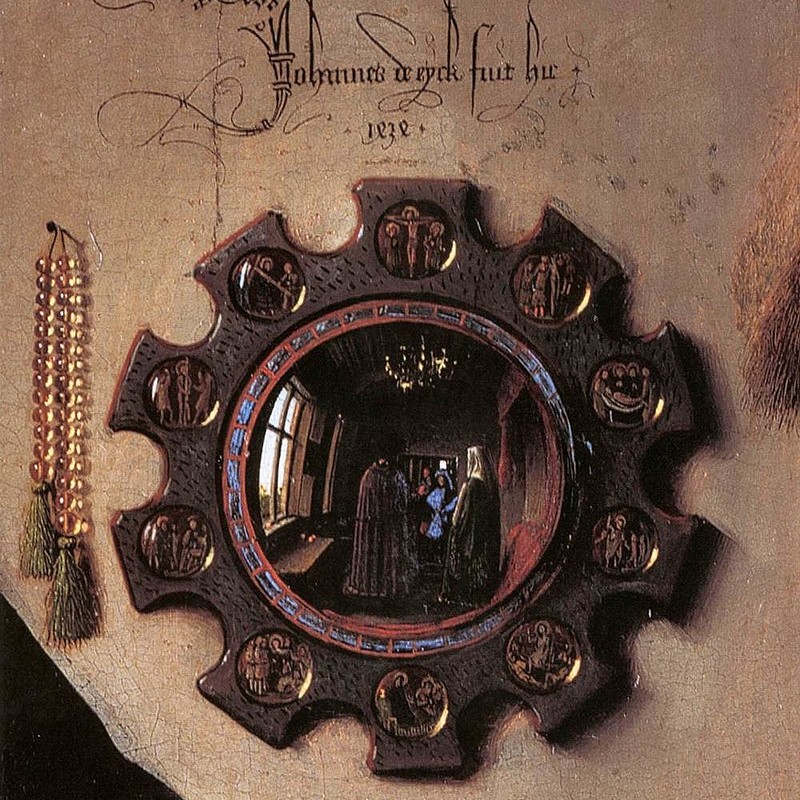

In Holbein’s famous Ambassadors painting, he uses an optical devise to remind us that any amount of worldly prestige and accumulation is largely irrelevant. Even the very wealthy should remember that death is haunting us. Marshall uses this same optical devise to show how the white-girl-beauty aesthetic quietly and insidiously haunts, even the rooms where black beauty is celebrated in earnest.

As a final, seemingly playful punctuation, Marshall shouts into history, proclaiming his arrival among the greatest masters in Western art by placing himself in the mirror opposite the viewer, in just the way that Van Eyke did in his famous wedding depiction.

The element that truly elevates Marshall’s painting is the fact that both children in the scene appear to notice the odd abstraction in the room and they are both puzzled by it.

Few things light me up this much. Thank you master Marshall!

John Singer Sargent and Tech N9ne

JOHN SINGER SARGENT AND TECH N9NE

These are among the most sharpened and focused technicians to touch any medium, across all genres. Both have mastered delivery of their medium with speed, and precision.

Sargent’s brush strokes when seen close reveal a very fast execution but at a distance they achieve near photographic precision.

Tech N9ne delivers precise and complex rap lyrics with super human speed.

I love both artists a great deal because I have such a love affair with technical facility but both lack a certain heart and nutritiousness and leave me feeling unsatisfied.

Notorious B.I.G.'s "I Got A Story To Tell" and Charlie Kaufman's "Adaptation"

NOTORIOUS B.I.G.’S “I GOT A STORY TO TELL” AND CHARLIE KAUFMAN’S “ADAPTATION”

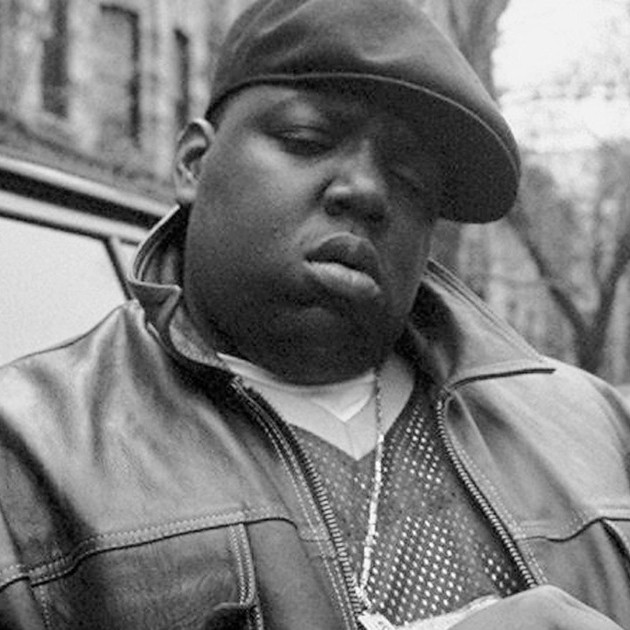

“I Got A Story To Tell” is a piece of art that carefully helps its audience understand the very complex delivery of a story.

The first half of the piece is executed in rap verse and tells of Biggie’s adventure leaving a club with a woman who was romantically involved with an NBA player (a fact that appears to be true). After sex, the two are relaxing when the basketball player arrives at home. In order to escape the situation, Biggie quickly stages a bogus robbery scene by tying the woman’s limbs and mouth (with her consent) and wrapping a scarf around his own face. He then threatens the man with a gun and escapes. This frees himself and the woman from the scrutiny of their infidelity.

At the middle of the song something very unusual happens. The second half of the song repeats the same story, this time as natural field audio, a casual conversation with friends which includes all the details of the same account, starting from the moment they leave the club to the moment he escapes. Rap (like most art) tends to be extremely difficult to understand for people outside of the culture, due to its speed and the complexity of the language. Presenting the song in this way is (whether intentional or not) a generous gift that invites us all and helps everyone understand it.

Adaptation does something similar. Charlie Kaufman transforms the story of “The Orchid Thief” into something entirely different and in many ways, far more complicated. In order to explain many of the substantial and largely abstract deviations from its source material, the film has fictionalized versions of Charlie Kaufman artificially inserted into the book’s narrative. This lets us see the process of making those deviations and partially explains them before they happen.

At a crucial turning point in the story, a writing mentor tells Kaufman the script is bad and the only way to salvage it would be to create a more sensational ending. This sets up a ridiculous, blockbuster 3rd act which is on the one hand intentionally stupid and on the other, a satisfying culmination of the film’s efforts to prepare us for such a conclusion.

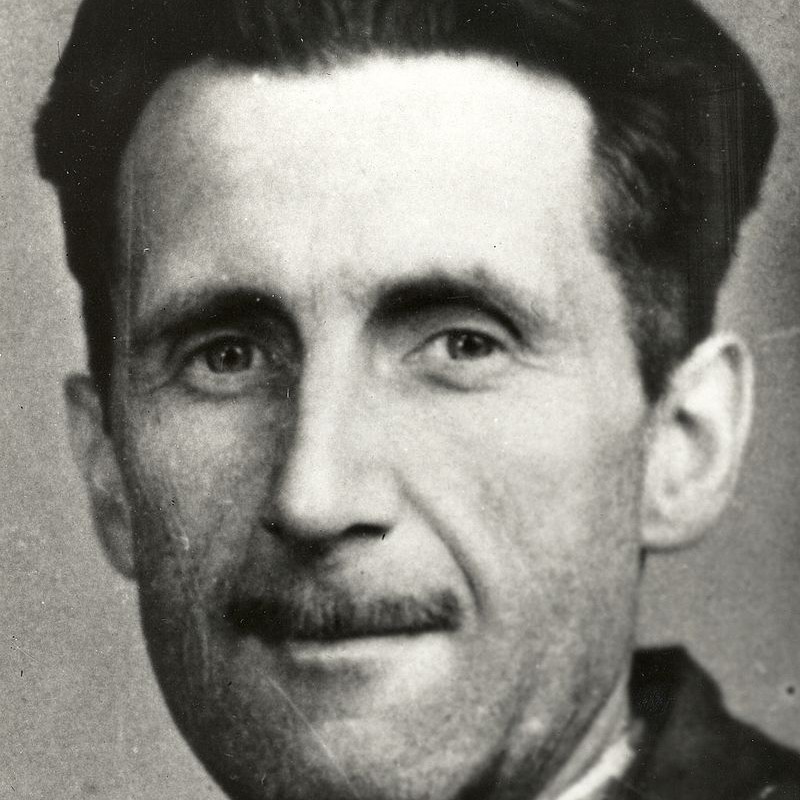

Oni Baba and 1984

ONI BABA AND 1984

These two pieces are beautiful triumphs of art that are ultimately indulgent fantasies into the most horrible parts of us. Both are expressions of utter bleakness, each ending with the total annihilation of its main character by evil. In both cases the conclusions are cynical, self-hating submission.

To be clear, I think both are beautiful masterpieces that help us to understand our own minds. But in the same way that many action movies or rap songs indulge in violence to that end, both are gratuitous explorations of misery and cruelty.

The old woman in Oni Baba lives a life of desperate scarcity, surviving on the killing and harvesting of fighting nobles. This lonesome, predatory existence eventually leads to the coercion and manipulation of her only companion out of jealousy. Its conclusion is this: If we masquerade as a monster to please our ego, we are irreparably transformed into that monster.

1984 describes a governing mechanism who’s size and strength has far surpassed any counter measures which would protect the minds and hearts of individuals. Its conclusion is this: Governments are capable of murdering love. In fact, the innermost love that resides in our center.

Both are important, brilliant explorations that are certainly not wrong in their assertions. They’re just not quite right either.