Shutter Island and the Old Woman/Young Woman Illusion

SHUTTER ISLAND AND THE OLD WOMAN/YOUNG WOMAN ILLUSION

The central character of Shutter Island is an FBI agent who arrives on a prison island reserved for mentally ill, criminal inmates. He is there to investigate a possible murder and escape. There is subsequently a conspiracy carried out to prevent him from finding the truth. Later the plot reveals that he might in fact be an inmate in the prison who is carrying out a delusional fantasy and the staff and inmates are playing along in hopes that he will have a psychic breakthrough.

It’s not a masterpiece but it’s a very good movie and it’s best quality is that it accidentally avoids the tedious boring devise known as “the twist ending.” Even the final decisive scene acts as a poignant conclusion to both possibilities.

Strangely however, the filmmakers seem to maintain that it is a “twist ending” (in interviews), preferring one scenario over another. But within the framework—internal to the film’s universe—every event, every interaction, every turn is designed carefully to fit into the logic of both of the two possibilities, regardless of the other. Scorsese is not entitled to some special, private intent which galvanizes one scenario over the other when every component is built so carefully to hold up both.

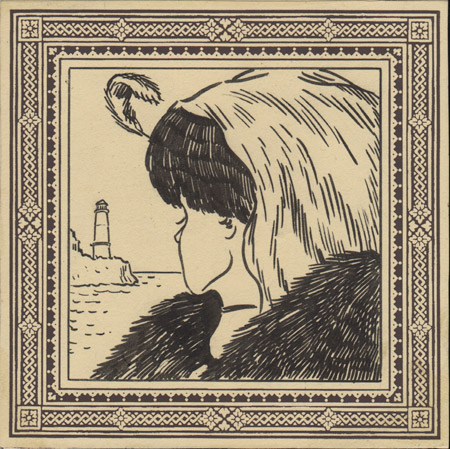

Assigning an ultimate trueness to one of the frameworks makes as much sense as saying that the famous optical illusion is factually a young woman but it is masquerading as an old woman. Obviously it is neither thing and both simultaneously, and it offers us a momentary relief from our relentless, desperate need for logical packaging.

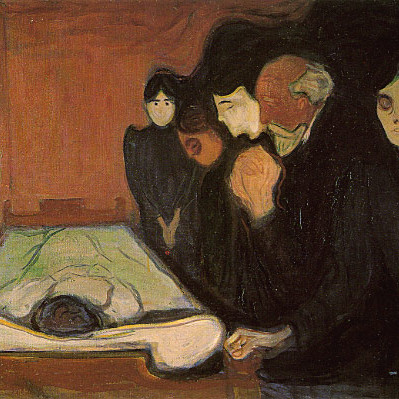

Kurt Cobain and Edvard Munch

KURT COBAIN AND EDVARD MUNCH

These two artists are the masters of sublimation, concerned with pain and isolation and mind sickness. They convert this sickness into something beautiful—a beauty that is comforting and oddly warm. It resonates with a rich texture that nonetheless maintains its intense anxiety and suffering.

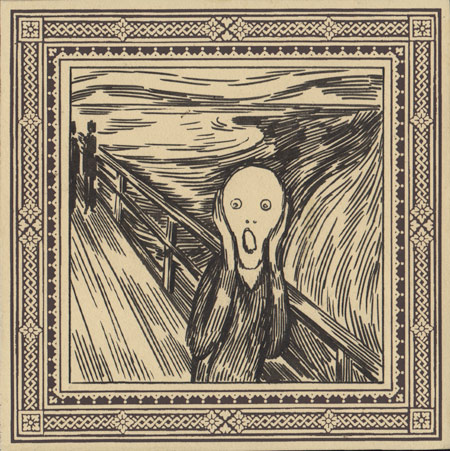

The screaming final lines of Nirvana’s Unplugged rendition of Lead Belly’s “Where Did You Sleep Last Night” cut into us as acutely as Munch’s most famous painting.

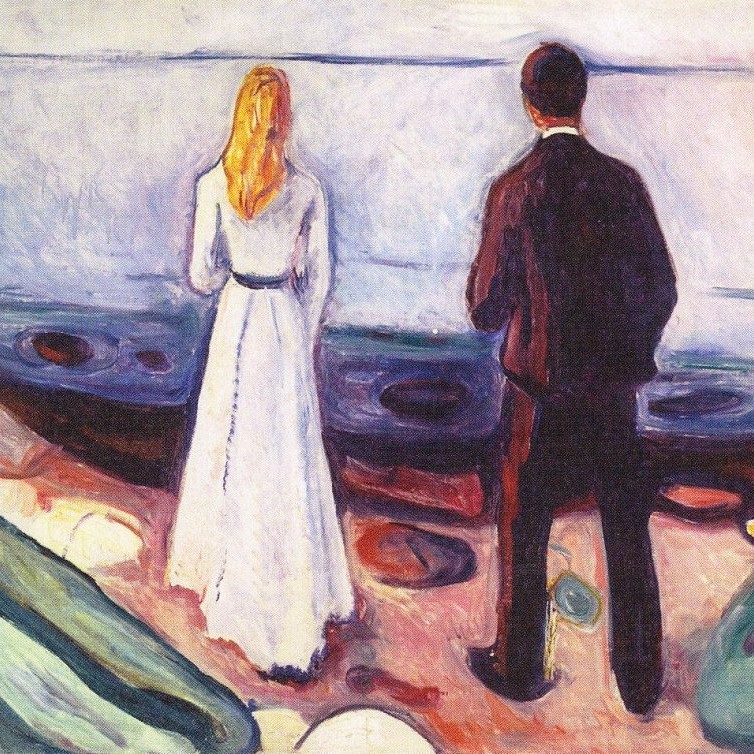

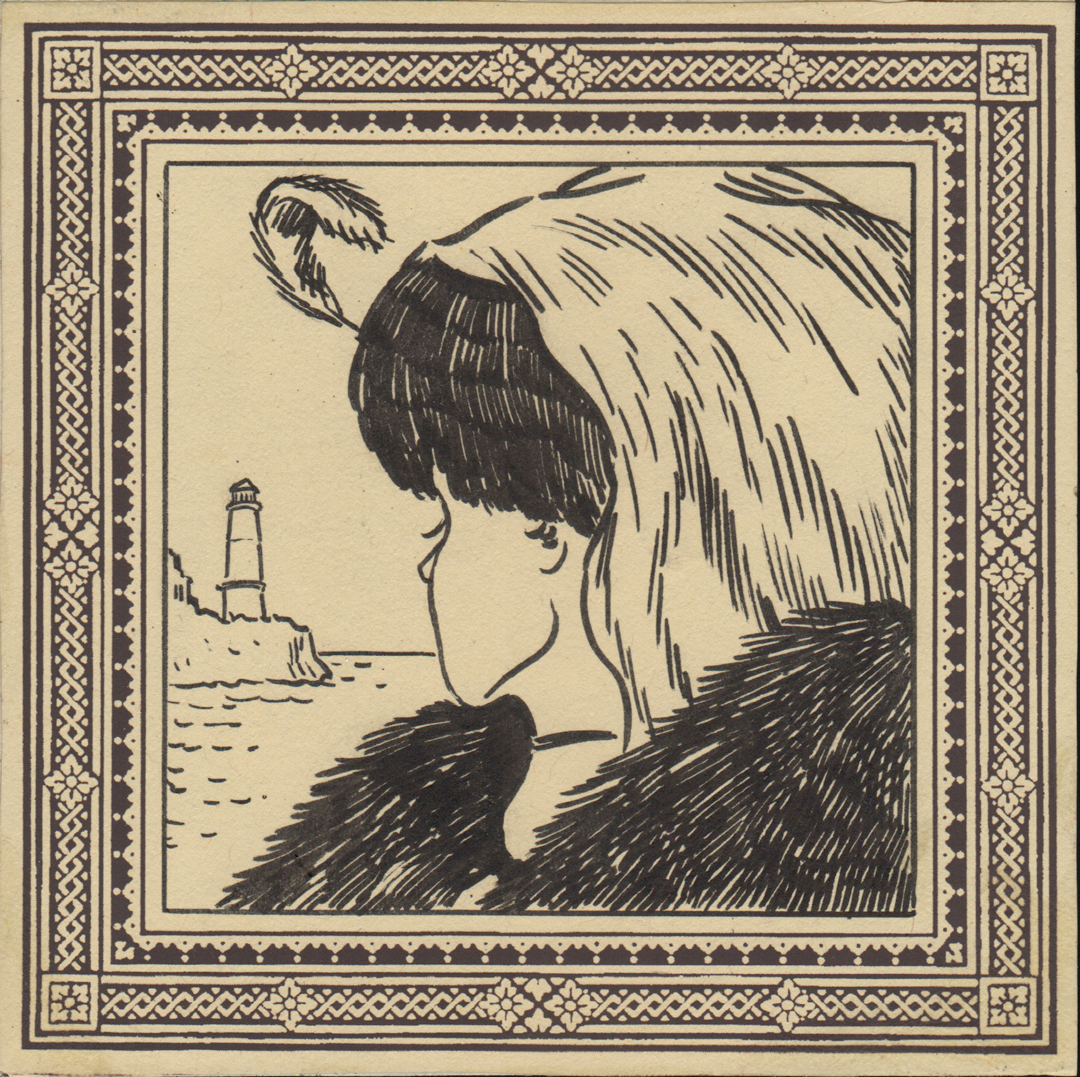

Munch’s piece Two Human Beings (The Lonely Ones) depicts desolate minds near each other with no hope of intimacy, while Cobain takes this bleakness even further in “Drain You.”

“One baby to another says, ‘I’m lucky to have met you… It is now my duty to completely drain you.'”

David Lynch and Kendrick Lamar

DAVID LYNCH AND KENDRICK LAMAR

These are two of the greatest living artists. Each feels a strong obligation to create ethical, uplifting art. Both deal with dark, unsettling ideas and situations, but in nearly every piece they put a great deal of weight on the side of emotional relief and moral goodness in explicit ways.

Other deeply ethical artists with dark subject matter (e.g. Stanley Kubrick and Cormac McCarthy) make their way to these positive ends by way of hardship and terror only, lacing the morality implicitly. Lynch and Lamar, on the other hand, carry us through these same, wretched, horrifying environments but at the end of the journeys they are generous with explicit sweetness and joy. And importantly, these elements are not bland, sentimental versions of positivity. In fact, the moments of redemption and goodness are often more heartbreaking, more overwhelming and more permanently altering than the moments of terrorism.

The forceful love of the old woman and the parents in Good Kid Maad City is a great example. The protection and vast humanity of so many of Elephant Man’s friends is another and these hit us harder than any of the brutal beatings or humiliations.

Even small, simple moments of relief do not feel like empty bits of sentimentality thrown in thoughtlessly. The awkward animatronic bird eating a bug at the end of Blue Velvet is so carefully strange as to be genuinely fun and comforting; a real bird would have had less effect. It acts as a playful reward. We need this reward too, having just been dragged through the nightmare of monstrous, sexual desperation.

Similarly, Kendrick ends his “Alright” video with a smile and a wink, laying dead in the street after being casually assassinated by a cop. With this wink, filled with so much joy and love, he leaves us with one last reminder that black Americans are among the most powerful and triumphant human beings on earth and they are indeed “going to be alright”.

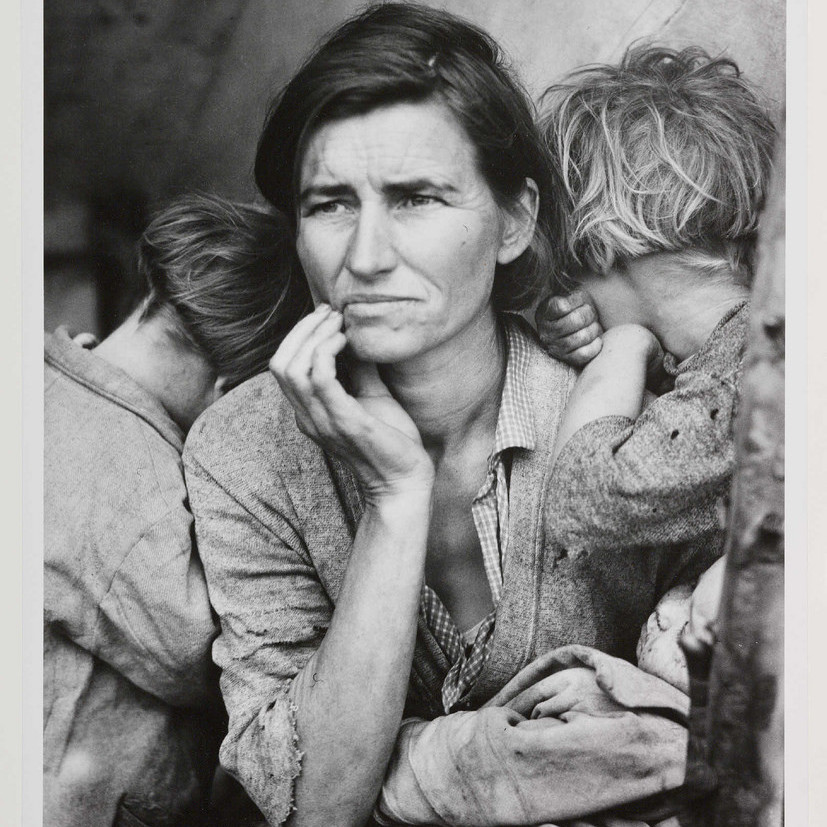

Dorothea Lange's "Migrant Mother" and Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux's "Ugolino And His Sons"

DOROTHEA LANGE’S “MIGRANT MOTHER” AND JEAN-BAPTISTE CARPEAUX’S “UGOLINO AND HIS SONS”

The greater context of each of these pieces is extremely different from one another. In the case of “Ugolino,” his hunger is punishment for a life full of greed for power, and his hunger appears to be paramount over that of his children. In the case of the “Migrant Mother “we know that she is the victim of a desperate moment in history and we assume that the hunger of her children is more important.

These two pieces are strikingly similar, however. As moments frozen in time, in the way that only sculpture and photography can manage, there is a calm exterior. But on the inside, we see the focus and fixation that churns in a frenzied mind, searching for some calculation that will alleviate the most urgent human problem.

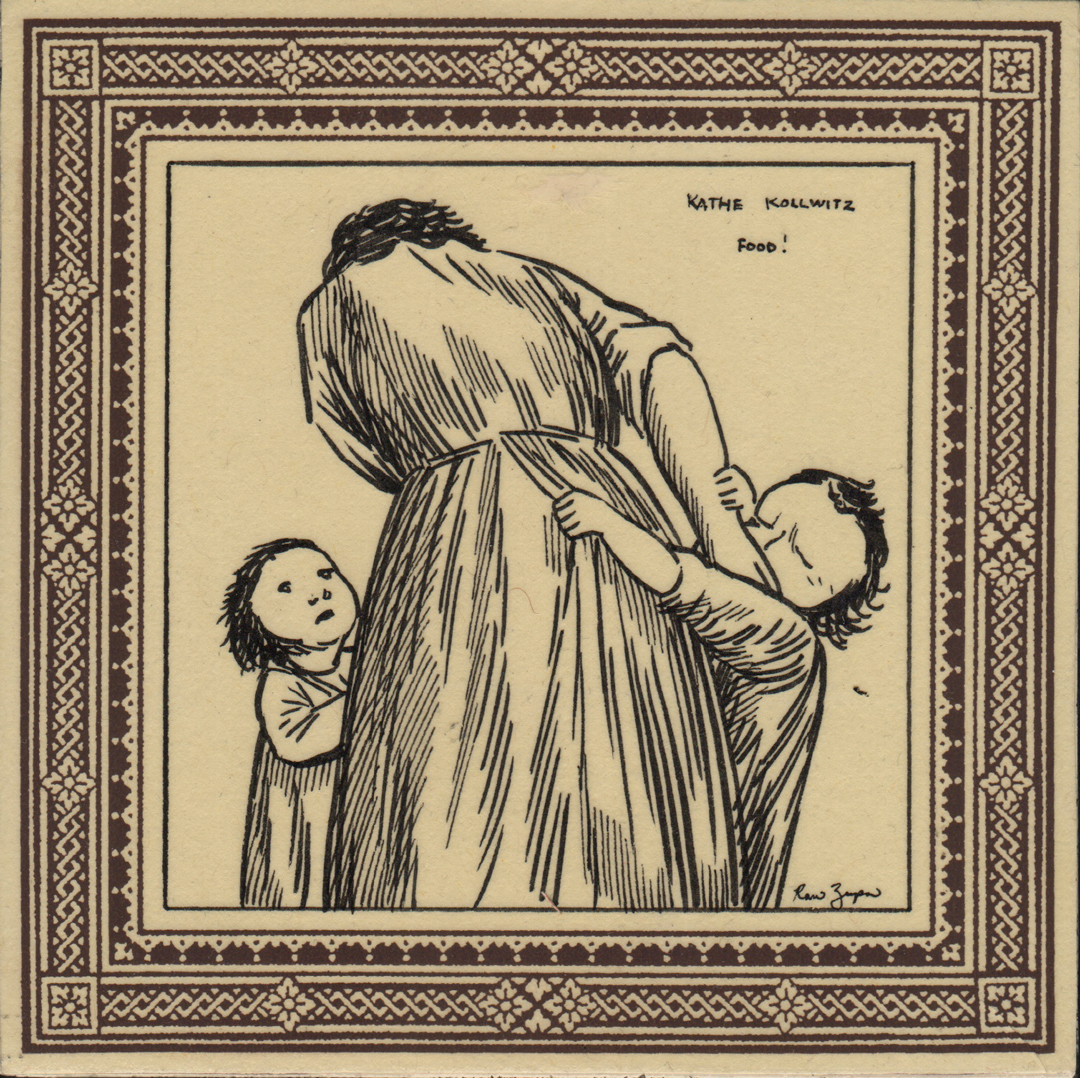

Hunger as a subject matter for art is deeply unsettling, especially for anyone who has experienced periods of real scarcity. This week’s drawing is my recreation of a beautiful Kathe Kollwitz print that I find particularly horrifying.

"Dead Man" and Bill Burr

“DEAD MAN” AND BILL BURR

For a handful of reasons, Jim Jarmusch and Bill Burr are deeply inspiring to many other artists in their respective disciplines. First, of course, is that they are both masters of their craft. But another component that has for many years set them apart is the ease with which they cross certain cultural boundaries. This kind of travel is often very well intentioned, but it is tricky and can sometimes feel clumsy and off.

“Dead Man” deals with the interface of Native Americans and White Europeans different from any film ever made. Bill Burr looks at the interface between black and white Americans, also in an entirely unique way.

Each appear to have little or no prescribed, preemptive filters built from fear, guilt or political calculation. They instead seem to be responding to dauntingly complex, painful realities with a surprisingly simple tool set: organic, responsive, optimistic honesty.